Central Illinois has had many major league baseball players in history. Let’s look at them from the 12 counties that we have selected to become Central Illinois. (Logan, McLean, DeWitt, Woodford, Fulton, Peoria, Mason, Tazewell, Cass, Morgan, Menard, Sangamon).

As I snooped around looking for information on Robert Kinsella, I happily stumbled upon an article about his dad and the connections to baseball and some names of baseball history that he interacted with on a daily basis.

Not to forget Richard (Bob), he played in four major league games for the New York Giants in 1919-1920. He made his major league debut on September 20, 1919 and played his last contest on October 2, 1920. He was 3-for-12 in his career

check out the other bios HERE.

==============================================================================================

This article is published with permission from the Sangamon County Historical Society. Check them out as they have some great research items and stories to read.

Richard Kinsella (baseball scout, team owner)

Richard “Sinister Dick” Kinsella (1862-1939) was a semi-pro baseball player, owner of Springfield’s Three-I League team and a well-known local politician. But he was famous nationally as the right-hand man of John J. McGraw, the Hall of Fame manager of the New York Giants from 1902 to 1932.

“Sinister Dick” got his nickname not because of skullduggery but because of his dark, bushy, intimidating eyebrows. (A sports writer reportedly once said “his eyebrows looked like fright wigs.”) Nonetheless, Kinsella was a tough, old-school baseball man.

He also was a shrewd judge of talent. As a scout – at first, in fact, McGraw’s only scout – Kinsella discovered dozens of major-league baseball players, including Hall of Famers Carl Hubbell, Frankie Frisch, Freddie Lindstrom, Mickey Cochrane, and Hack Wilson. He may also have been involved in McGraw’s signing of Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity; Kinsella said he and McGinnity once played on the same team in Springfield.

Kinsella played first base during his own on-field career, which apparently was spent with town teams; businesses like the Illinois Watch Factory, Myers Brothers department store, local railroads and others sponsored teams during the period. The Illinois State Journal hinted at his playing style in an 1897 story involving a feud between Kinsella and Springfield Mayor Marion Woodruff: “Kinsella has been a power in Democratic politics in Springfield ever since the days when he played baseball and the bleachers went wild over the manner in which he stole second (base).”

Kinsella served on the Sangamon County Board of Supervisors and then was county treasurer from 1898 to 1902. He was a delegate to several Democratic national conventions, including serving as sergeant-at-arms at the 1912 convention. He also operated Kinsella Paint and Varnish for more than 50 years in Springfield.

Kinsella was among the early boosters of local minor-league baseball, starting at least in 1890 when a group of businessmen tried to raise money to support Springfield’s team in the Central Interstate League. The Springfield Senators had finished second in the Central Interstate in 1889. However, the league did not resume in 1890.

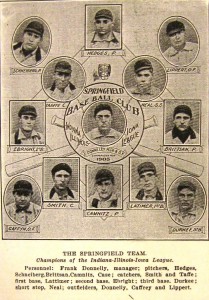

Springfield Senators, 1905; player-manager Frank Donnelly in the center. Despite references to the Senators being “champions,” the team actually finished third in the league in 1905. (Sangamon Valley Collection)

Kinsella later became a director of the Springfield Baseball Association, which sponsored a team in the Three-I League beginning in 1903. That first team was the Springfield Foot Trackers, according to baseball-reference.com; the name changed in 1904 to the Springfield Hustlers and then back to the Senators in 1905.

Most sources on Kinsella report that he became the owner of the Springfield franchise in 1904, but that is incorrect. Harry Jones owned most of the stock of the Springfield Baseball Association until fall 1905, when Kinsella challenged allegedly improper payments to the association’s secretary – Jones – and its treasurer. The legal dispute was settled in November 1905, with Kinsella paying $5,000 for 80 percent control of the team, according to newspaper reports.

As owner (or what newspapers called “the Springfield magnate”), Kinsella put together a winning organization, and the Senators were league champions in 1908 and 1910. However, his approach was to churn the team’s roster, hiring promising prospects and then, once they showed potential, selling their contracts elsewhere. Critics, many of them his Three-I competitors, said that was unfair and damaging to the league.

The Illinois State Register also crossed swords with Kinsella in 1910. Angered when the newspaper reprinted a St. Louis item suggesting Kinsella had assaulted an umpire – actually, he apparently had come to the ump’s defense – he barred Register reporters from League Park, the field at 11th Street and Black Avenue where the Senators played. The ban was to apply, Kinsella said, even if the reporters bought tickets and even at games not involving Three-I teams. (Town leagues also used the park.)

The Register responded in a June 16 commentary, one perhaps written by “sporting editor” Jimmie Dix, who was the special object of Kinsella’s ire.

If Dick Kinsella wants to run a baseball nine, that’s all right. He is a baseball genius in the picking of players and organizing pennant-winning teams. The State Register prints the news about it. Dick Kinsella’s business in this matter is running a ball nine. The State Register’s business is printing the news. We owe that to our 17,000 subscribers, not one of whom has ever made a request that we let Dick Kinsella tell us who we shall send to report the news or how we shall report it.

Despite the Senators’ on-field success, attendance at League Park in 1910 fell short of the Three-I League’s minimum of 35,000 patrons.

Meanwhile, Kinsella had begun scouting for McGraw’s Giants in 1907. So when he was offered the chance in 1910 to head the St. Louis Browns scouting organization, Kinsella put the Senators up for sale. Getting no solid offers in Springfield, he moved the franchise to Decatur in May 1911; that December, he sold out to another Springfield syndicate, once again headed by Harry Jones.

After scouting for the Cardinals, Kinsella joined the New York Yankees staff in 1916. He later returned to the Giants organization.

Jim Sandoval, writing for the Society for American Baseball research, outlined Kinsella’s scouting secrets.

Kinsella … subscribed to newspapers in every town or city that had professional baseball. He made connections with the compilers of league statistics to get the official averages in advance of publication. He also acquired lists of players on waivers.

Kinsella once signed a player, Benny Kauff, by taking a job on a plantation near a Mississippi resort where the player and other baseball figures were holding meetings, Sandoval wrote: “While the baseball people were meeting, Kinsella was meeting secretly with Kauff.”

Sandoval debunks another characteristic Kinsella story, that he once bought the contract of a prospect for $25 and a bird dog. Kinsella did give the dog to St. Louis Cardinals manager Roger Bresnahan, but as a gift, not as part of a player deal, Sandoval wrote.

However, Kinsella was part of a spectacular brawl at a St. Louis hotel in 1915. The fight grew out of an argument between Giants catcher Larry McLean; Sandoval describes the result:

As many as six players helped Kinsella. Accounts say two chairs were broken on McLean, with Kinsella breaking a rocking chair over his head, then chasing him around the fountain in the courtyard. McLean ran away, chased by McGraw and Kinsella, and McLean escaped by jumping into a passing automobile.

Kinsella retired from scouting in 1930. He remained active in politics, however, and ran Henry Horner’s Sangamon County campaign for governor in 1932. In return, Horner in 1933 named Kinsella director of the state division of oil inspection, a job he held till his death in 1939.

Long-time Illinois State Journal sports editor Bob Drysdale remembered Kinsella in his “Dope Bucket” column on Oct. 15, 1939:

One of the best – and greatest – of baseball’s old guard was called out by the Great Umpire last night when Richard F. (Dick) Kinsella died. Mr. Kinsella, more than anyone else, brought baseball fame to Springfield. As a player, manager and scout, he put this city in the forefront of the game. Stars discovered by him as a scout for the New York Giants have become baseball immortals. … He saw the game grow. He helped it to grow. If scouts ever gain their deserved recognition and win places in baseball’s Hall of Fame, Richard F. Kinsella will lead them all. He was the best.

Notes

*The Rippon-Kinsella House, the Kinsella family home at 1317 N. Third St., is listed on the National Register of Historic Sites. As of 2015, it was a bed-and-breakfast home.

*Richard Kinsella and his wife Mary Kathryn had four sons, three of whom died as young men. The fourth, Robert (1899-1951), played in four games for the New York Giants in 1919 and 1920.

*Some biographies give Dick Kinsella credit for building Springfield’s first baseball stadium. That appears to be overstated. League Park was created in 1902, and the grandstand was built in 1903 and improved in 1904. As a director of the Springfield Baseball Association, Kinsella no doubt played a role in the construction, but he didn’t take control of the Springfield team until late 1905. League Park’s grandstand and bleachers were destroyed by an arson fire in June 1911, a couple of months after Kinsella moved the team to Decatur. (Kinsella later wrote that he moved the team because of the fire; that was incorrect.)

The site of League Park, after lying vacant for decades — for many years, it was a periodic circus and carnival grounds — is again a baseball facility. Renamed David Lawless Park and operated by the Springfield Park District, it is the home of four diamonds.